“Carry Burkittsville at any cost”:

Burkittsville, Crampton’s Gap and the Maryland Campaign

by Matt Borders

Invasion:

Following the Confederate victory of 2nd Manassas at the end of August 1862, Confederate General Robert E. Lee moved the Army of Northern Virginia towards the Potomac River near Leesburg, Virginia. On September 3, Lee sent a letter to Confederate President Jefferson Davis laying out the reasons for an advance across the river, the unofficial border between the United States and the Confederacy.

The David Arnold farm was established in 1789. David Arnold operated the farm in 1862 where much of the fighting of the Federal left wing took place.

The present seems to be the most propitious time since he commencement of the war for the Confederate Army to enter Maryland. The two grand armies of the United States that have been operating in Virginia, though now united, are much weakened and demoralized…

I therefore determined, while threatening the approaches to Washington, to draw troops into Loudoun, where forage and some provisions can be obtained, menace their possession of the Shenandoah Valley, and, if found practicable, to cross into Maryland. The purpose if discovered, will have the effect of carrying the enemy north of the Potomac, and, if prevented, will not result in much evil.

The army is not properly equipped for an invasion of an enemy’s territory. It lacks much material of war, is feeble in transportation, the animals being much reduced, and the men are poorly provided with clothes, and in thousands of instances are destitute of shoes. Still, we cannot afford to idle, and though weaker than our opponents in men and military equipments, must endeavor to harass if we cannot destroy them. I am aware that that the movement is attended with great risk, yet I do not consider success impossible, and shall endeavor to guard it from loss…1

Lee’s reasons to begin the Confederate invasion of the North were many. As stated in his proposal, he hoped to draw the Union army into Maryland, north of the Potomac River, away from Virginia. This would give northern Virginia farmers a rest from the war by allowing the Army of Northern Virginia to live off the enemy for the season. He was also looking to the politics of Maryland, a border state, and the potential of gaining said state for the Confederacy, although the likelihood of this had already been downplayed by Colonel Bradley Johnson, originally from Frederick, Maryland. Additional political considerations included the mid-term elections occurring throughout the north that fall, and the ever-present possibility of European recognition and intervention. All this however hinged on a Confederate military victory north of the Potomac River.2 The stakes were extremely high, but Lee believed his army, which had campaigned and won throughout the summer of 1862, could deliver such a victory.

Maryland, My Maryland:

The Confederate advance into Maryland began on September 4, with the division of Major General Daniel Harvey Hill crossing the Potomac at several locations, including Point of Rocks, Noland’s Ferry and Cheek’s Ford. The advance scattered the token forces guarding the Potomac River crossings and Hill’s men went to work disrupting the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal. While the canal was cut, in several places, its waters draining into the Potomac, the aqueduct at the mouth of the Monocacy River proved just too strong for the limited tools at the Confederates disposal.3 These efforts continued into September 5, when Hill moved on, heading north towards Monocacy Junction and Frederick, Maryland.

With a toe hold now in Maryland, the main crossings began on September 5 with Major General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson’s wing of the Army of Northern Virginia crossing the Potomac at White’s Ford around noon. Jackson had been advocating for an advance into Maryland for some time and was pleased to be underway. His forces were also enthusiastic about the opening of the campaign, as each regiment reached the Maryland side of the river, their band struck up the song “Maryland, My Maryland”.4

Though Lee’s incursion into Maryland was underway, it had not gone unnoticed. As previously mentioned, D.H. Hill’s command had dispersed Federal pickets along the Potomac and Confederate cavalry, crossing below Jackson on September 5 at Edward’s Ferry, soon spurred forward to Poolsville, Maryland. There, Brigadier General Fitzhugh Lee’s brigade drove off a mixed company of the 1st Massachusetts Cavalry and some of the first casualties of the Maryland Campaign were suffered by both sides.5 The next day, as Major General James Longstreet’s wing began to cross at White’s Ford, the Confederate cavalry moved east to Parr’s Ridge, establishing a series of vedettes or outposts along the elevation and the communities in its immediate vicinity. This screen allowed the Army of Northern Virginia to continue to move into Central Maryland unimpeded and kept watch for the approach of Federal forces from the east.6

![Charge of the Sixth Corps of the Union Army from Burkittsville toward Crampton's Gap (George T. Stevens, Three Years in the Sixth Corps [Albany, NY: S.R. Gray, 1866], 136)](https://burkittsvillepreservation.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Charge-of-the-Sixth-Corps-Senior-Staff-300x192.png)

Charge of the Sixth Corps of the Union Army from Burkittsville toward Crampton’s Gap (George T. Stevens, Three Years in the Sixth Corps [Albany, NY: S.R. Gray, 1866], 136)

North of Poolsville, and on the far east side of Frederick County, stands Sugarloaf Mountain. Since September 3, the United States Signal Corps had been watching the Confederate build up near the Potomac fords and the subsequent crossings from that elevation. These observations were signaled back to other stations and eventually telegraphed to Washington. This crucial source of information could no longer be ignored by the Confederate advance. On the morning of September 6, as his brigades were going into position along Parr Ridge, Major General James Ewell Brown (JEB) Stuart personally led a column of cavalry towards the prominent height. Spotting the Confederate advance, Lieutenant Brinkerhoff N. Miner, who commanded the small station of Sugarloaf, ordered his position abandoned. The high ground of Sugarloaf was occupied by the Confederates and Miner and one his men were later captured a few miles from the mountain.7

Throughout September 6, Robert E. Lee’s forces advanced towards the important crossroads town of Frederick, Maryland. At the same time, problems were beginning to mount for Lee and his army. The first was the physical condition of the Confederate high command. By September 6 both Lee and Jackson were moving through the Maryland countryside in ambulances. The Confederate commanding general had been yanked off his feet on August 31 by his horse. Catching himself, he badly sprained one wrist and fractured the other.8 With both arms in splints it was impossible for Lee to ride, and he spent much of the Maryland Campaign traveling in an ambulance or being led on horseback. Jackson had his own equine accident on the morning of September 6. He had been gifted a fine new mount by an admirer when his forces entered Maryland. As neither animal nor rider were familiar with each other, when Jackson put spurs to the gift horse it reared back, falling on the Confederate Left-Wing commander, leaving him prostrate for half an hour. Though he spent most of the day in an ambulance wagon, he was back in the saddle by that evening.9 In addition to these dangerous injuries, James Longstreet was also partially incapacitated with a painful boil on his foot.

Beyond the injuries to Lee and his inner circle, the other problem developing was the Federal reaction to the first Confederate invasion of the north. At the opening of the campaign the Army of Northern Virginia, by moving into central Maryland, had interposed itself between Washington DC and the Federal garrisons in the northern Shenandoah Valley. The largest of which was Harpers Ferry. The former weapons manufacturing town and Federal arsenal had been cleaned out by Confederate forces at the beginning of the war,10 but had since been retaken and was an important depot, helping supply Federal incursions into Virginia. Lee had believed that Harpers Ferry would be abandoned, but by September 7, that had yet to happen, and he proposed to Longstreet that he lead an expedition against the garrison to either drive it off or capture it. The commander of Lee’s Right Wing voiced his concerns about breaking up the Confederate army while in their opponent’s territory and felt the “venture not worth the game.”11

The Federal Reaction:

As Longstreet’s forces, following Jackson’s, filtered into vicinity of Frederick, Maryland over September 7 and 8, forty miles to the south, Federal forces around Washington DC were stirring. The defeat of Major General John Pope’s Union Army of Virginia at 2nd Manassas had rocked the National Capital, some fearing that Confederate forces would press on for Washington. With Pope’s army straggling into the defenses of the capital and the Army of the Potomac already there however, the likelihood of a full-on Confederate attack was unlikely. 12 Instead, on September 2, 1862, President Abraham Lincoln called upon his former General-in-Chief and current commander of the Army of the Potomac, Major General George B. McClellan. That day McClellan was given command of all forces in and around Washington DC, that included, his army – the Army of the Potomac, Pope’s army – the Army of Virginia, and the Washington garrison. He was to take these disparate commands and merge them into one force, the reconstituted Army of the Potomac, and defend the nation’s capital. When it became clear that Confederate forces had entered Maryland, this mission was expanded to protecting Baltimore as well and driving Lee from Maryland. By September 5, the Army of the Potomac began to move.13 The Federal response the Lee’s invasion had begun.

Upon entering Maryland, Robert E. Lee had believed he would be able to not only operate in the state, but that the abandonment of positions in the Shenandoah Valley and elsewhere by Federal forces, to concentrate in Washington, gave him the time he needed to do so.14 This was quickly proven false as the vanguard of the Army of the Potomac, clashed with Lee’s rearguard at several points on September 8. Just four days after the Confederate invasion began, there was significant cavalry skirmishing at both Poolesville and Hyattstown, Maryland. These fights however tend to be overshadowed by the entertainment exploits of Confederate Major General JEB Stuart during this period and his famed ball at the Landon Female Academy in Urbana, Maryland. There he and his officers brought some of the pageantry of war to the small village, the festivities though were interrupted by the clash the 1st North Carolina Cavalry with the 1st New York Cavalry at Hyattstown. Stuart rode off into the night only to find the fight was essentially over when he arrived. This allowed him to return to his ball and the music and dancing continued well into the early morning hours of September 9.15Major Heros von Borcke of Stuart’s staff later admitted, “The sun was high in the heavens when we rose from our camp pallets the following day.”16

The Lost Orders:

On September 9 Stuart found Lee camped two miles south of Frederick, Maryland near Monocacy Junction. Lee’s headquarters camp was amongst the wood lot of the Best Farm along the Georgetown Pike. From there he had dictated a proclamation to the people of Maryland the previous day, written by Bradley Johnson, about the intensions of the Confederate Army and pledging that the forces under his command would be on their best behavior while in the state.17 Stuart’s news of the Federal approach however placed the Army of Northern Virginia in a difficult situation. With McClellan approaching from the east and the Union garrison at Harpers Ferry under Colonel Dixson S. Miles to his south, Lee chose to divide his command in an attempt to neutralize the Harpers Ferry garrison while drawing off the Army of the Potomac to the northwest. He did this by dictating an order that had a significant impact on both sides for the rest of the campaign, Special Orders 191.

Special Orders 191 has often been misidentified or referred to as a battleplan. It was not. Special Orders 191 was a marching order for the Army of Northern Virginia that sent just over half of the army, under General Jackson, to deal with the Harpers Ferry garrison, while the rest of the army, under General Longstreet, continued west, towards Hagerstown, Maryland drawing the Federal army away from their base of supply at Washington. This order was written on September 9 and the army began to move out the next day. The divisions of Major General Ambrose Powell (A.P.) Hill, along with those of Brigadier Generals John R. Jones and Alexander Lawton had the furthest to go and led off the march on the morning of September 10. This column of Jackson’s was to cross back over the Potomac River into Virginia, approaching Harpers Ferry from the west. Additional divisions, those of Major Generals Lafayette McLaws, Richard Anderson and Brigadier General John Walker were sent to aid Jackson by taking the crucial Maryland and Loudoun Heights, thus closing the routes of escape and trapping the Federal Garrison at Harpers Ferry. None of the columns closing on Harpers Ferry had an easy task, nor did they have a lot of time, for the original deadline of completion for Special Orders 191 was set for Friday, September 12.18

With Jackson on the road and Longstreet’s divisions, Brigadier General’s David R. Jones and John Bell Hood following with the reserve artillery, the division of Major General Daniel Harvey (D.H.) Hill was tasked with the rearguard of the army. Stuart’s cavalry had the very tail end of the Confederate advance, to sweep up any stragglers that could not keep up.19 With the advance begun it took several days for the entire Army of Northern Virginia to pass through Frederick. Diarist Jacob Engelbrecht noted that Confederate troops passed by his shop in Frederick all day on September 10 and for a few hours the next morning, estimating that it took 17 hours all told for the whole army to move through the city.20

By September 12, the last Confederates were headed west out of Frederick as the lead elements of the Union IX Corps, on the right of the Federal advance, entered the east side of the city. There was a brief clash in the streets that drove out the Confederate cavalry allowing the IX Corps, along with the Federal cavalry under Brigadier General Alfred Pleasonton, to occupy the Frederick and its various approaches.21 Moving down the National Road, also known as the Baltimore Pike, the IX Corps was the most northern element of the Union army’s advance. On the opposite end of the line, the left flank, was the VI Corps, commanded by Major General William Franklin, moving roughly parallel to the Potomac River. By the end of September 12 nearly the entire Army of the Potomac was closing on Frederick, Maryland with the I, II & XII Corps occupying the roads between the flanks and the V Corps trying to catch up having just been released from the Washington defenses.22 Once again, the city of Frederick was a concentration point for an army.

Throughout September 13 thousands of Federal troops massed around Frederick waiting their turn to pass through and beyond the city. Where the Confederate presence in the City of Clustered Spires had been received in a very sullen manner, Frederick was now awash in flags and cheers as the Army of the Potomac began to move through.23 McClellan too was wildly lauded, by both his soldiers and the citizenry of Frederick:

Sixth Corps Senior Staff on the Peninsula, 1862. Seated L-R: Joseph J. Bartlett, Henry W. Slocum, William B. Franklin, George W. Taylor (killed August 27th & replaced by Torbert), and John Newton [National Archives]![Sixth Corps Senior Staff on the Peninsula, 1862. Seated L-R: Joseph J. Bartlett, Henry W. Slocum, William B. Franklin, George W. Taylor (killed August 27th & replaced by Torbert), and John Newton [National Archives]](https://burkittsvillepreservation.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Sixth-Corps-Senior-Staff-300x178.png)

General McClellan came into the town upon the central road, and such an ovation as greeted him! It was very different from Virginia. The people were overjoyed. Flags were displayed upon all the houses. There were all sizes and descriptions; large flags suspended across the streets, and little sixpenny flaglets waved by girls and boys, all of whom had been subject to the general contagion which pervaded every one.24

While a portion of the IX Corps, was ordered west through Frederick to assist General Pleasonton’s cavalry skirmishing in the Catoctin Mountains, it was the II Corps which had the honor of passing through Frederick in its entirety first. It was as the II Corps was tramping north along the Georgetown Pike towards Frederick that the XII Corps arrived outside the city at around noon having marched on a parallel road and over open fields. The XII Corps, at that time commanded by Brigadier General Alpheus Williams, had been marching from Ijamsville, Maryland since 7am. They forded the Monocacy River at Crum’s Ford and advanced to within sight of Frederick. The Corps was led by skirmishers from the 27th Indiana Infantry. When orders came to halt and stack arms so that the XII Corps could wait its turn to march through Frederick, Company F of the 27th Indiana found itself in the remains of a Confederate camp. Amongst the detritus of war, Corporal Barton Mitchell found an orders envelope in which was a letter and two cigars. Passing the bundle to Sergeant John Bloss, the contents were read by him. A copy of Lee’s marching order, Special Orders 191, had been found. Bloss recognized the importance of the document and passed it up the chain of command. The orders first went to Colonel Silas Colgrove, who commanded the 27th Indiana, who then took them to his brigade commander, Brigadier General George H. Gordon, who ordered Colgrove to take the documents to the headquarters of the XII Corps. There, Colonel Samuel Pittman, the Adjutant General for Brigadier General Alpheus Williams received the orders. Both Pittman and Williams read the orders and recognized the importance of the documents. Williams ordered Pittman to take the “Lost Orders” to General McClellan.25

The impact of Special Orders 191 on McClellan’s plans had more to do with confirming his suspicions than rewriting his campaign. By September 13, McClellan had been receiving reports for at least a day of the Confederate army dividing and moving in different directions. Special Orders 191 not only apparently confirmed this, but also revealed the Confederate columns most likely destinations, Harpers Ferry, Virginia and Boonsboro, Maryland.26 It may also have verified, in McClellan’s mind anyhow, that the Army of Northern Virginia outnumbered the Union army by a large margin and due to this Lee felt confident enough to divide his forces in enemy territory. As Special Orders 191 had said nothing of Lee’s actual troop strength, McClellan hoped that by getting between Lee’s divided columns he could negate the Confederates supposed numeric advantage and destroy them in detail.27

Burkittsville:

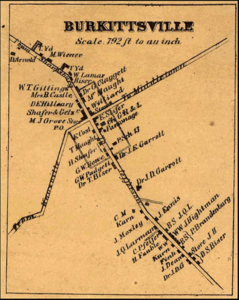

The Isaac Bond Map of 1858 showing the existing buildings and ownership of the properties. Note that St. Paul’s Lutheran Church, which was built in 1859, is not shown.

With Brigadier General Alfred Pleasonton’s cavalry and the IX Corps already pursuing the Confederates into the Middletown Valley, destined to strike Lee’s rearguard at Fox’s, Frosttown and Turner’s Gaps, McClellan turned to Major General William Franklin’s VI Corps in hopes of relieving the Federal garrison at Harpers Ferry. At 6:20pm on September 13, McClellan ordered Franklin to advance at daybreak to Burkittsville, Maryland and to take Crampton’s Gap just west of the town. “Having gained the pass, your duty will be first to cut off, destroy or capture McLaws’ command and relieve Colonel Miles.”28 Franklin was also ordered not to wait for elements of the IV Corps, which was trying to catch up to him, but instead press on to Crampton’s Gap. These instructions, while straight forward, were ambitious, as the VI Corps was camped just to the east of the Catoctin Mountains approximately eleven miles from Burkittsville.29

The Village of Burkittsville was quiet on September 13 but had recently hosted three brigades of Confederate Major General Lafayette McLaws’ division as it moved south crossing into the Pleasant Valley by way of the Brownsville Gap. The gap, which begins three quarters of a mile southwest of Burkittsville, was an easier assent than the steep grade of Crampton’s Gap, a mile to the north, and got the Confederates that much closer to their objective. That objective was the strategically important Maryland Heights, the southernmost point of Elk Ridge on the west side of the Pleasant Valley. This high ground dominated Harpers Ferry and the other ridge lines around it. McLaws summed up the importance of this position in his after-action report of the Maryland Campaign, “So long as Maryland Heights was occupied by the enemy, Harper’s Ferry could never be occupied by us. If we gained possession of the heights, the town was no longer tenable to them.”30

While the head of McLaws column passed into Pleasant Valley on September 11, his entire command did not. At least three brigades, those of Brigadier General’s William Barksdale and Joseph Kershaw, as well as Colonel William Parham’s, all camped in near Burkittsville on the night of September 11. The Confederate presence in and around Burkittsville was brief however with the last of McLaws command passing through Brownsville Gap to the village of Brownsville by mid-morning on September 12.31 With the majority of McLaws command heading for the Maryland Heights there was very little thought given to covering the South Mountain Gaps and thus the rear of Confederate forces closing on Harpers Ferry. This mistake was only realized on the morning of September 14, as the VI Corps passed over the Catoctin Mountains through Mountville Pass, making its way down the mountain to Jefferson, Maryland.

Preparation for Battle:

General William Franklin had the VI Corps moving by 6am on September 14, with the intention of following McClellan’s instructions from the previous night. His command likely reached Jefferson, Maryland by mid-morning. Encouraged by the enthusiastic welcome from the citizens and wanting to let the IV Corps catch up to his column, Franklin lingered in Jefferson until around 11am, after which he pushed on.32

Approaching Burkittsville along the Jefferson Road by noon, General Franklin was under orders that if he found Crampton’s Gap defended he was to make dispositions for an attack and begin half an hour after he heard the guns to the north, where the rest of the Army of the Potomac was forcing the upper gaps.33 The problem was that firing had likely been heard all morning as the initial skirmishing at Turner’s Gap had started around 6am and by 9am the fighting at Fox’s Gap was well underway. Upon his approach, Franklin later reported that he found the Confederates strongly posted at Crampton’s Gap and immediately prepared for an attack.34

The defense of Crampton’s Gap however was not as daunting as it seemed. While Lafayette McLaws’ division was a formidable force, most of his command was involved in isolating and taking Harpers Ferry, only the small brigades of Brigadier General Paul Semmes and Colonel William Parham were on hand to potentially contest the Federal advance over South Mountain. Semmes was convinced that the Federals main effort would be towards Brownsville Gap and posted his brigade there. He then utilized Parham’s brigade to picket Crampton’s Gap as well as Solomon’s Gap, on the west side of Pleasant Valley. Parham spent the night of September 13 at the summit of Crampton’s Gap conferring with Colonel Thomas Munford’s cavalry, but on the morning of September 14, he chose to leave the 16th Virginia Infantry on the east side of Crampton’s Gap, just outside Burkittsville and march the rest of his command back to Brownsville. When the VI Corps’ 13,000 men began to arrive east of Burkittsville there was only roughly 1000 Confederates guarding the mile and a half from Brownsville Gap to Crampton’s Gap.35

The Federal advance down the Jefferson Road was not contested until just outside Burkittsville, earlier that morning. Union cavalry, moving ahead of the infantry column, had come under fire two miles outside the village and had fallen back to the skirmishers of the 96th Pennsylvania Infantry for aid. Companies A and F advanced and were within a mile of Burkittsville by noon. The rest of the 96th Pennsylvania quickly caught up with company A along Distillery Lane, while company F succeeded in entering Burkittsville, driving back the dismounted troopers of the 2nd Virginia Cavalry. The Pennsylvanians advanced stubbornly down Main Street, past the churches and across the Middletown Road, gaining the western edge of the village where they established a new skirmish line.36 As the initial skirmishing was wrapping up, and the Confederate artillery at Brownsville Gap was making its presence known, the divisions of William Franklin’s VI Corps began to arrive about a mile from the village. Franklin himself was near the head of the column and chose the farm of Martin T. Shafer, on the corner of the Jefferson Road and modern-day Catholic Church Road, as his headquarters. There the Federal infantry pressed slightly closer to Burkittsville and then turned off the Jefferson Road near the estate of Ortho Harley, dropping into a slight ravine through which Burkitt’s Run passes. This had the advantage of concealing the massing infantry from the guns in Brownsville Gap and soon hundreds of small fires were going as the men prepared coffee and their mid-day meal.37 The defenders of Crampton’s Gap were given a reprieve, but for how long?

As Franklin’s command was settling in for lunch, both the Confederate defenders of Crampton’s Gap and Major General George McClellan were acting. The artillery fire from both Brownsville and Crampton’s Gaps had alerted the 10th Georgia Infantry, which had been picketing the roads in Pleasant Valley near Crampton’s Gap, as well as Colonel William Parham, who began to make the trek back to the gap with the 6th and 12th Virginia Infantries. Colonel Thomas Munford was the senior officer present at the time and ordered Parham’s 16th Virginia Infantry down the east face of South Mountain to take position along Mountain Church Road behind the stone fences facing Burkittsville. The 16th Virginia stretched across Main Street where it intersects with Mountain Church Road and had the dismounted troopers of the 2nd Virginia Cavalry to their right. On the opposite flank, most of the 10th Georgia Infantry, eight companies, fell into line behind the same stone fence. The 12th Virginia Cavalry was also present guarding the Arnoldstown Road. Shortly after 12:30pm Parham’s 6th and 12th Virginia regiments arrived and were also advanced to the stone fence along Mountain Church Road between the 10th Georgia and 16th Virginia.38 Time was of the essence and the Confederates were using it to their advantage.

McClellan on the other hand, wanted General Franklin to press the attack. About the same time Confederate reinforcements were arriving, a courier from Middletown found Franklin’s headquarters. Having received intelligence regarding Crampton’s Gap that morning, McClellan urged Franklin to attack and to, “continue to bear in mind the necessity of relieving Colonel Miles if possible.”39 The arrival of Confederate reinforcements however had not gone unnoticed and at 12:30pm Franklin shot back a quick reply to his commander, “I think from appearances that we may have a heavy fight to get the pass.”40 Franklin however wanted to rest his command and allow time for his divisions to close up. A lull then settled over the fields around the village of Burkittsville as both sides prepared their forces for the eventual advance.

The advance turned out to be some time in coming. Outside Burkittsville, Major General William Franklin, his staff and his senior commanders settled onto the grounds of the Shafer Farm for lunch, cigars and a lengthy discussion on what to do next. The two divisions of the VI Corps were also allowed to rest during this period and by midafternoon the tactical discussion had reached an impasse. When Franklin asked Major General Henry Slocum, the commander of the 1st Division, who would lead the attack, Slocum responded that the 2nd Brigade would lead. As such Colonel Joseph Bartlett, commanding the brigade, was called upon to have a say in the matter. Bartlett had not spent the warm afternoon idling away his time, he had been actively reconnoitering the approaches to Crampton’s Gap. When asked by General Franklin as to what side of the Jefferson Road should be used to advance, Bartlett was quick to say the right. That was all Franklin needed to hear and so the hammer of the VI Corps would fall north of the Jefferson Road. As it was his troops that were to spearhead the assault, Bartlett asked what tactical formation they would advance in. General Slocum was interested in his subordinate’s thoughts on the matter and wanted to hear Bartlett’s suggestions. The 27-year-old New York lawyer recommended the division advance by column of brigades, meaning a line of two regiments in front and two in back for all three brigades and go straight at the gap. Slocum approved the formation and the commanders moved off to implement it.41 About the same time the plan for Crampton’s Gap was being formulated, Major General McClellan again demanded an advance, writing at 2pm, “Mass your troops and carry Burkittsville at any cost… If you find the enemy in very great force at any of these passes, let me know at once, and amuse them as best you can, so as to retain them there.”42

Major General William B. Franklin

Major General Henry Slocum later recorded in his after-action report that, “At 3 p.m. the column of attack was formed… each brigade being in two lines, the regiments in line of battle and the lines 200 yards from each other…”.43 As stated, Colonel Joseph Barlett’s brigade led the way, moving down through Burkittsville and turning right out of town near the Middletown Road. Each of Slocum’s three brigades moved as quickly and quietly as possible into the large fields just northeast of Burkittsville and deployed into their column of brigades. Bartlett later wrote, “About 4 o’clock p.m. I ordered forward the twenty-seventh New York Volunteers… to deploy as skirmishers… My skirmishers found the enemy at the base of the mountain, safely lodged behind a strong stone wall… Halting behind a rail-fence about 300 yards from the enemy, the skirmishers were withdrawn and the battle commenced.”44

Battle of Crampton’s Gap:

Besides the limited communication with the rest of the Army of the Potomac, the fighting at Crampton’s Gap was entirely separate from the rest of the Battle of South Mountain. The VI Corps was on its own and not coordinating with other elements of the Federal army during the battle. All the while the Confederate defenders, like those in the northern gaps, were heavily outnumbered, but had a significant terrain advantage. Hoping to aid in this defense were Confederate reinforcements from Brigadier General Howell Cobb’s brigade, they had been ordered to Crampton’s Gap by Major General Lafayette McLaws when word had reached him about the arrival of Federal troops outside Burkittsville. Cobb was to take over command of the defense of Crampton’s Gap when he arrived, holding the gap, “if he lost his last man doing it.”45 The problem was time, as Cobb’s men were camped at Sandy Hook, Maryland on the Potomac River, just over eight miles away from Crampton’s Gap.

With the 1st Division, VI Corps deployed in front of Crampton’s Gap and the Confederate line on Mountain Church Road, Major General Henry Slocum’s orders were simple, a direct advance across the rolling fields outside Burkittsville, driving the Confederates from the stone fences, up into Crampton’s Gap and beyond.46 Elements of Major General William F. Smith’s 2nd Division advanced directly through Burkittsville and up the Gapland Road into Crampton’s Gap, the two divisions converging on the gap near the top of South Mountain. Brigadier General William T. H. Brooks Vermont Brigade led this second column and linked the 2nd Division to Slocum’s Division by coordinating their advance through Burkittsville with that of Colonel Alfred Torbert’s New Jersey Brigade to their right. Supporting the push through Burkittsville was Colonel William Irwin’s brigade. One of his men, Major Thomas Hyde of the 7th Maine Infantry, vividly recalled the fighting towards Crampton’s Gap:

As our column got to the little town of Burksville, we could see Slocum’s, our first division, in line and apparently about to force the passes, when the smoke of a battery on the far mountain side was soon followed by round shot shrieking overhead. We were ordered to take the double-quick, and through the streets of Burksville we went, while cannon balls crashed through houses, and the women, the young and old, with great coolness, waved their handkerchiefs and flags at us… Slocum’s people went right up the pass, driving all before them, and we were close after, in support, having all the excitement and exhilaration of a fight without its usual bloodshed.47

After the initial skirmishing and maneuvering of forces east of the Mountain Church Road, General Slocum’s entire division, three brigades of mostly veteran infantry, lurched forward around 5:30pm. Colonel Torbert’s New Jersey troops slammed into the Confederate line near the intersection of Mountain Church Road and Main Street, while to their left the 4th and 2nd Vermont of Brooks Brigade swept away the dismounted troopers of the 2nd Virginia Cavalry. To Torbert’s right, Colonel Bartlett’s brigade had been overtaken by the New York and Pennsylvania troops of Brigadier General John Newton. By the time Newton’s men had crossed the last 300 yards to the Confederate line they had redeployed into one long line of battle, taking the center of the Confederate position. As Newton hit the center, the last regiment of Colonel Bartlett’s brigade, the 96th Pennsylvania Infantry, swung around the left flank of the Confederate line, unhinging the 10th Georgia from the Mountain Church Road. With their center assailed and both flanks threatened the Confederate line began to break, falling back up South Mountain towards Crampton’s Gap.48

The Confederate reinforcements of Brigadier General Howell Cobb’s Brigade arrived in Crampton’s Gap right about the same time the Federal attack hit home. Cobb threw two of his regiments, the 24th Georgia Infantry and Cobb’s Legion, down Gapland Road to stem the Federal advance and buy time for the men of Colonel’s Thomas Munford and William Parham’s commands to rally. This counterattack was enveloped by the on-rushing New Jersey troops of Torbert’s Brigade and both Confederate regiments suffered terrible casualties and collapsed, Cobb’s Legion at one point being nearly surrounded. The 15th North Carolina Infantry and 16th Georgia Infantry were sent down the Arnoldstown Road when they arrived, also in hopes of buying time for their comrades to rally. They were on higher ground, above Whipp’s Ravine, through which the Federals were passing, and their initial fire staggered the Federal line. This did not last long however and soon the Federal line was surging forward once again taking advantage of the collapse of Cobb’s other regiments, the Federal flank was secure and could focus solely on the North Carolina and Georgia troops along Arnoldstown Road. These regiments were soon flanked themselves and sent running back up through Crampton’s Gap. By 6:30pm the entire Confederate line was in retreat.49

Though the Confederate defense was collapsing, one last tragedy befell the defenders of Crampton’s Gap before the day was over. As Brigadier General Howell Cobb was desperately trying to rally the fleeing Confederates in Crampton’s Gap itself, a section, two guns of the Troup Light Artillery, arrived in the gap. Cobb deployed the guns one pointed down Gapland Road, the other down the Arnoldstown Road, as he rallied elements of several regiments behind a stone fence on the west edge of Padgett’s Field within Crampton’s Gap. The Federal advance, due to the speed of it and the rough, difficult terrain, had broken down into masses of troops, as opposed to organized regiments, moving up Gapland Road and Whipp’s Ravine. The Confederate guns, each of which were named by their crews, began to boom, trying to repulse or slow the Federal advance. Facing the New Jersey Brigade was “Sallie Craig”, while the gun looking down the Arnoldstown Road and Whipp’s Ravine was called “Jennie”. Both guns fired nearly point blank into the converging Federal masses, but as the Union troops got within 75 yards, the guns limbered up and retreated west down the mountain away from Crampton’s Gap. The retreat of the Troup Light Artillery was the last straw, though Cobb’s rag-tag line tried to hold and continued to fire across Padgett’s Field, the return fire from the Jersey Brigade forced them to breakoff and follow the guns down the mountain. During the retreat the Confederate guns had stopped to fire into their pursuers, but the New York and Pennsylvania troops forced the guns to once more limber up. It was at this point that the “Jennie” broke an axle and was abandoned. The gun was captured by the 95th Pennsylvania Infantry, as they continued to press down the mountain, only to be later claimed by the 2nd Vermont Infantry who was following the pursuit. As the Federals pressed their pursuit down into Pleasant Valley around 7pm the fight for Crampton’s Gap was over.50

Aftermath:

The lead elements of the VI Corps passed through Crampton’s Gap during the pursuit and set up camp near the foot of the mountain in Pleasant Valley. The Confederate defenders had fallen back in disarray towards Brownsville, where a new line was desperately established by General Cobb. Major Heros Von Borcke, riding with Major General JEB Stuart, later described the scene:

The poor General was in a state of the saddest excitement and disgust at the conduct of his men. As soon as he recognised us in the dusk of the evening, he cried out in heartbroken accents of alarm and despair, “Dismount, gentlemen, dismount, if your lives are dear to you! the enemy is within fifty yards of us; I am expecting their attack every moment; oh! my dear Stuart, that I should live to experience such a disaster! what can be done? what can save us?51

While General Cobb’s reaction to the situation was understandable, it proved to be unnecessary, for the VI Corps vanguard did not press the attack on the September 14. Nor did the entire VI Corps when it arrived in Pleasant Valley the following day. General Franklin instead secured Rohrersville and was concerned about the line Cobb had thrown together with additional troops from McLaws’ Division across the valley floor. The VI Corps remained in Pleasant Valley watching McLaws until the night of September 16, when it was ordered to rejoin the Army of the Potomac, then gathering along the banks of Antietam Creek.52

For the men of the VI Corps, they felt they had done something important, even if they had not reached Harpers Ferry in time. Major Thomas Hyde spoke for many in the corps when he described the fighting at Crampton’s Gap:

On the whole, this battle at Crampton’s Gap was very credible to our arms. We had three thousand men actually engaged, and the enemy two thousand; but ours had to climb up to them, which more than made up the difference. We got four flags and four hundred prisoners, and General Franklin could congratulate himself upon a successful encounter, — well planned and quickly over.53

The Cost:

No battle, no matter how successful, is ever fought without loss. The fighting at Crampton’s Gap cost 1495 casualties, 533 Federal and 962 Confederate.54 Before the fighting was even over Surgeon William J. H. White, Medical Director of the VI Corps, established Hospital “A” in the large brick home of Henry McDuell, just north of Burkittsville. Once the hospital was up and running, Surgeon White moved into Burkittsville proper where many public and private buildings were used to cover and care for the wounded. The Resurrection German Reformed Church was designated Hospital “D”, while it is speculated that St. Paul’s Lutheran Church and the parsonage for the Reformed church and were Hospitals “B” and “C”. With the hospitals established and the walking wounded already coming in, the process of collecting those who could not transport themselves off to the Burkittsville began.55 The wounded of both sides were treated in these hospitals and the dead of both temporarily buried on the farms around Burkittsville and near the hospitals themselves. These however proved to be temporary burials, for the vast majority of the Federal dead were disinterred in 1867 and were placed in Antietam National Cemetery. The Confederate dead remained around Burkittsville for a few years longer until they too were taken up and placed in the Confederate section of Rose Hill Cemetery in Hagerstown, Maryland. There is little doubt that these burials, and reburials, were incomplete and that some of the dead of both sides remain today in the rough terrain of South Mountain, forever tied to Crampton’s Gap and the village of Burkittsville.56

Burkittsville.

1 The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Series 1, Vol. 19, Part 2, pp. 590-591

2 Joseph L. Harsh, Taken at the Flood: Robert E. Lee & Confederate Strategy in the Maryland Campaign of 1862, (Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 1999), 25, 48-50, 81-82.

3 D. Scott Hartwig, To Antietam Creek, The Maryland Campaign of September 1862, (Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012), 94-95 & 98.

4 Ezra Carman, The Maryland Campaign of September 1862, Vol I: South Mountain, (El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2010), 90-91; Heros Von Borcke, Memoirs of the Confederate War For Independence, Vol I, (Edinburgh & London, UK: William Blackwood & Sons, 1866), 185.

5 To Antietam Creek, 102-104.

6 George B. Davis, Leslie J. Perry, Joseph W. Kirkley, The Official Military Atlas of the Civil War, (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1891-1895), 94, Plate 27-1.

7 To Antietam Creek, 108-109.

8 Taken at the Flood, 78.

9 James I. Robertson, Stonewall Jackson: The Man, The Soldier, The Legend, (New York, NY: MacMillan Publishing, 1997), 587-588.

10 E.B. Long, The Civil War Day by Day: An Almanac 1861-1865, (New York, NY: Da Capo Press, 1971), 68.

11 James Longstreet, From Manassas to Appomattox, Memoirs of the Civil War in America, (Philadelphia, PA: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1896), 201-202.

12 John J. Hennessy, Return to Bull Run: The Campaign and Battle of Second Manassas, (New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, 1993), 451.

13 The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Series 1, Vol. 19, Part 1, 25.

14 Taken At The Flood, 114-117.

15 Laurence H. Freiheit, Boots & Saddles: Cavalry During the Maryland Campaign of September 1862, (Iowa City, IA: Camp Pope Publishing, 2013), 160-161 & 168.

16 Heros Von Borcke, Memoirs of the Confederate War For Independence, Vol I, (Edinburgh & London: United Kingdom, 1866), 198.

17 Taken at the Flood, 125.

18 The Maryland Campaign of September 1862, Vol I: South Mountain, 114-115.

19 Timothy Reese, Sealed With Their Lives – The Battle of Crampton’s Gap, Burkittsville, Maryland, September 14, 1862, (Baltimore, MD: Butternut & Blue, 1998), 11-12.

20 Jacob Engelbrecht, The Diary of Jacob Engelbrecht, 1818-1878, (Frederick, MD: The Historical Society of Frederick County, 1976), 948-949.

21 OR Vol. 19, Part 1, 416.

22 Taken at the Flood, 209-210.

23 “Domestic Intelligence. The Rebel Invasion of Maryland.”, Harper’s Weekly, September 27, 1862, 611.

24 “McClellan at Frederick”, Harper’s Weekly, October 4, 1862, 626.

25 Gene M. Thorp & Alexander B. Rossino, The Tale Untwisted – George McClellan and the Discovery of Lee’s Lost Orders, September 13, 1862, (El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2019), 12-14.

26 OR Vol 19, Part 2, 270 – 271.

27 Ethan Rafuse, McClellan’s War, (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2005), 292.

28 OR Vol 19, Part 1, 45.

29 Sealed With Their Lives, 33.

30 OR Vol 19, Part 1, 852-853.

31 Sealed With Their Lives, 38.

32 Ibid., 44.

33 OR Vol 19, Part 1, 45 – 46.

34 Ibid., 374-375.

35 Sealed With Their Lives, 51.

36 To Antietam Creek, 439.

37 Sealed With Their Lives, 58-59.

38 Bradley M. Gottfried, The Maps of Antietam, An Atlas of the Antietam (Sharpsburg) Campaign, Including the Battle of South Mountain, September 2-20, 1862, (El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2012), 76-77.

39 The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Series 1, Vol. 51, Pt 1, 833.

40 Stephen Sears, The Civil War Papers of George B. McClellan, Selected Correspondence, 1860-1865, (New York, NY: Da Capo Press, 1998), 460.

41 To Antietam Creek, 441.

42 OR Vol 19, Part 1, 46.

43 Ibid., 380.

44 Ibid., 388 – 389.

45 Ibid., 854.

46 To Antietam Creek, 447.

47 Thomas W. Hyde, Following the Greek Cross or Memories Of The Sixth Army Corps, (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press edition, 2005), 92 – 93.

48 The Maps of Antietam, 82 – 83.

49 To Antietam Creek, 465 – 467.

50 Maps of Antietam, 88 – 89.

51 Memoirs of the Confederate War For Independence, Vol I, 217.

52 OR Vol 19, Part 1, 47.

53 Following the Greek Cross, 93.

54 The Maryland Campaign of September 1862, Vol I: South Mountain, 310 – 312.

55 Sealed With Their Lives, 188 – 191.

56 Sealed With There Lives, 218 – 219, 221.